Ⅰ. A Brief Overview of the history of Hamletian Film Adaptations

Shakespeare’s plays have been shown on cinema screens almost paralleling with the invention of film. Hamlet is probably the most frequently adapted one. Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays started with silent films. The earliest version of Hamlet adaptation is the 59-minute British Hamlet with Johnston Forbes-Robertson by director Hay Plumb. Sven Gade’s Hamlet, A Drama of Revenge (Germany, 1920) makes Asta Neilsen play Hamlet who is actually a woman. However, it was not until the synchronized sound was invented that Hamlet could be more properly shown on screen, because one major part of the Shakespeare glamour is the language. The first full-length Shakespeare sound film is The Taming of the Shrew (USA, 1929) by Sam Taylor. As for Hamlet, it has been adapted over and over again. Directors who created their own Hamlet include Laurence Olivier (Britain, 1948), Tony Richardson (British, 1969), Franco Zeffirelli (USA, 1990), Kenneth Branagh (British, 1996) Michael Almereyda (USA, 2000), etc. Not only in Britain and U.S., Hamlet has been adapted by filmmakers from all over the world.

Of all those Hamlet films, Olivier’s version, winning four Oscars, the Grand International Prize of Venice in 1948 and two Golden Glove Award including Best Foreign Motion Picture and Best Actor, seems to be the most famous one. Almereyda’s 2000 version is perhaps one of the most controversial ones.

Ⅱ. Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet

A Film or Just a Filmed Play

On the narrative level, this adaptation has something different from the original play. Olivier cut the political subplot of Fortinbras and the two characters Rosencrantz & Guildenstern. In terms of running time, it is trimmed into two and a half hours from the original’s over four hours’ staged performance. This was made so to differentiate it from theatre as a film. Olivier’s own judgment of the film is a “rattling good story, inside and outside Hamlet’s mind, told cinematically.” However, the original text is still well kept; more importantly, it still gives us a stagey feeling.

The stagey feeling mainly comes from the engraving-like mise-en-scène. The castle and the lobby are all quite “prop-like”, especially for modern audience. The use of light is also similar to the lighting in theatre. High contrast of light and dark, the use of follow spot, these are all typical in theatre lighting. Not only the environment, but also the characters are quite theatrical. The performance of actors in this film, like other films at that time, was still greatly influenced by traditional theatre. Olivier himself was an excellent theatre actor.

However, Olivier was not content to make a mere filmed play; this film is full of cinematic terms. One notable example is the deep focus cinematography. Olivier was for sure influenced by Citizen Kane. In the scene depicting the reaction of Claudius to Mousetrap, the camera winds about the room, gradually revealing the reactions of different people, creating a tension that could not be conveyed in theatre. This is a good example of its great camera work and staging of actors. Olivier also uses the film medium to achieve dramatic effects that are not possible on the stage. During the “to be or not to be” soliloquy, Hamlet moves back and forth between speaking the lines on screen and thinking them in his head via voiceover.

Figure 1: Hamlet observes Ophelia through an arch of the castle, example of deep-focus cinematography

In this film, we see constant oscillation between theatre and cinema. The mise-en-scène, the lighting and the exaggerated performance remind us of the theatrical part of the film; exploiting various shot scales, camera movements and angles, it is still a successful filmic adaptation. It’s a hybrid of theatricality and cinematography.

Scene Analysis

The first scene I’d like to talk about is the opening scene. When the credits are rolling, the background is a surging sea and the blurry image of the castle. Right after that is the full shot of the castle in bird’s eye view. The castle is kind of surrounded by misty air, with the low-keying lighting, giving us a feeling of mystery and eeriness. Then Olivier speaks in voiceover, the text rolling on the screen. After the quote from the play, Olivier gives his own comment, “This is the story of a man who could not make up his mind.” It’s intriguing that the image come together with this sentence is actually the very last moment of the whole film, in which a central tower comes into view and four soldiers are carrying Hamlet’s body. Then the soldiers and Hamlet dissolve while the tower remains, naturally flashing back to the beginning of the story. Another important element in this scene is the solemn and stirring music. The symphony, along with all those elements mentioned above, helps to set the basic tone of the film. The tragic atmosphere of the play is largely strengthened.

Figure 2: The Elsinore Castle at the opening shot.

Another interesting scene is in the bedchamber where Hamlet and his mother have a quarrel. The scene is evidently separated into two parts by the ghost’s reappearance. At first, Hamlet is obsessed by rage, using the dagger to threaten his own mother. The tragic result of his rage is the death of Polonius. But after the ghost appears again, Hamlet’s murderous actions turn into tenderness. Before parting, they passionately embrace and kiss, directly on the limps, twice. A similar scene has already surprised me at the beginning of the play at the wedding ceremony of Claudius and Gertrude, where the queen also kisses Hamlet on the limps. Olivier obviously exaggerated the oedipal overtones of the play. Another piece of evidence is that Eileen Herlie, the actress playing the queen, was only 28 then while Olivier as Hamlet was 41. They appear pretty much the same age on screen. On the other hand, Ophelia’s role as the lover seems to be greatly weakened.

Figure 3: Two scenes that Hamlet and Gertrude kiss each other on the limps.

Ⅲ. Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet

A Modern American Interpretation

Almereyda’s Hamlet takes place in modern New York City. Denmark turns into the conglomerate with Claudius as the CEO, and Elsinore the hotel where the family stays. Hamlet himself has become a young man interested in making films with a DV. The hostile takeover upcoming from Fortinbras is reported on the front page of USA Today. Modern elements like hip-hop culture, corporate politics, video cameras, faxes, stretch limos, fine wines, cool architecture and really nice suits are all over the film. But the basic story remains the same, and fortunately, Almereyda left the language alone, except for some necessary changes and reductions to make it a 2 hour film. The lines, however, are fashionably delivered in a flat and plain way, probably in an attempt to situate Hamlet in a contemporary audience and make the viewing experience more natural. Almereyda has created a new standard for adaptations of Shakespeare, with an understanding of its new period and setting.

Scene Analysis

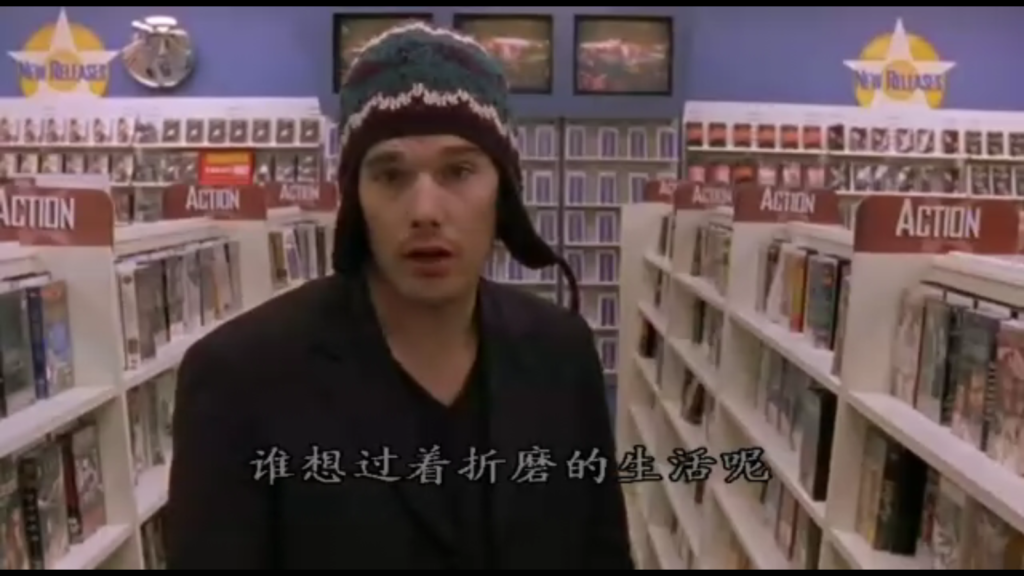

Personally, the most interesting scene in this film is the “to be or not to be” soliloquy. This soliloquy is delivered when Hamlet walks in the aisles of a Blockbuster video store, where powerful music is being played and the monitor on the wall shows a video clip full of violence and explosions. The most notable visual factors in this scene are the Action movie signs. It seems the store only gets action films. When Hamlet walks down the aisle, he is surrounded by these signs with “ACTION” on them. If, in the traditional play, we feel Hamlet’s delay through all his words and behaviors, then in this 2000 filmic version, Almereyda intentionally uses visual language to show us the sarcastic contradiction between his thought and his delay directly. Color is another visual element. In this scene, blue seems to be one dominant color; the wall of the store is painted blue. This might also embody Hamlet’s melancholy. With the blue wall as the background, the red “ACTION” signs are even more striking.

Figure 4: Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy in the video store

Another tricky change is the Mousetrap scene. The play-within-a-play is now the film-within-a-film. As mentioned above, Hamlet in this film is a DV maker. So he makes the short video Mousetrap very much like an experimental film. His film includes the clips from The Devil-Doll (1936) and East of Eden (1955). The former is about a doll-maker’s effort to infantilize his victims to revenge; the latter is a tragedy of youth’s conflicts with repressive parental control. Apparently, this Hamlet feels that he has been infantilized by his mother and uncle and he is willing to fight against it. In Mousetrap we are also shown a clip from Deep Throat (1972), which is a notorious porn movie. He uses this to satirize his mother and uncle. The film Mousetrap, compared to the play Mousetrap, is more aggressive and direct. If Hamlet in the original play uses the device of Mousetrap to make sure whether Claudius is the murderer, the filmmaker Hamlet seems not only wants to certify, but also means to directly attack.

Figure 5: A frame from the video clip Mousetrap by Hamlet

Ⅳ. Conclusion

Olivier’s Hamlet is generally a conservative adaptation. We can see clearly the influence of traditional theatre from the setting, the mise-en-scène and the performance of actors. But Olivier reaches a good balance between theatre and cinema by successfully applying many cinematic tools. Almereyda’s Hamlet is more self-sufficient. Except for the basic narrative and the carefully cherished lines, the locale, the background of the story, the characters and their performances all changed.

Every director has his own Hamlet. The two Hamlets are inevitably influenced by the directors themselves and the culture of their time. In Olivier’s Hamlet, the utilization of high-contrast black and white and low-key lighting is typical practice in American film noir. The setting and props in this film is more all less influenced by German Expressionism which was prevalent in 1920s and 1930s. Olivier’s attention on Oedipus complex in Hamlet-Gertrude-Claudius relationship can find its root in Freud’s theory. In Almereyda’s version, more modern world concerns are covered. Through all those skyscrapers and commercial bands, we see the domination of commercialism; the setting of the film depicts a claustrophobic environment; the infantilization of Hamlet and Ophelia brings out the issue of generational alienation. On the whole, Almereyda offers a postmodern picture of the Hamlet story.

Up to now, there has been at least more than 50 Hamlet films produced worldwide. Every time a version comes to our sight, we make comparisons with the original play and other classical film adaptations. No matter how successful it reproduces the glamour of Shakespeare, or how “weird” it is altered, every director’s Hamlet adds to the archive of this everlasting art treasure.

References:

孟宪强,《三色堇——<哈姆雷特>解读》,商务印书馆,2007;

施小萍,《后现代语境下的电影改编》,2004;

姚凌燕,经典文本的现代演绎——论莎剧《哈姆雷特》的电影改编,2005;

贾智,论奥利维尔与阿尔莫雷达对《哈姆雷特》的文学挪用,2010;

罗吉·曼威尔著,史正译,《莎士比亚与电影》,中国电影出版社,1984;

David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson, Film History, 影印第2版 ,世界图书出版公司,2012;

Internet Movie Database, www.imdb.com;